We Heart Consent: A Recipe for Better Memorable Messages or Conversation Hearts

Ingredients

A space for approximately 10 people to meet comfortably around one large or several smaller tables.

Paper for participants to respond to exercises

Heart-shaped paper cut-outs

Pens /pencils

Markers

Large sheets of paper or prints-outs of the definitions of consent

Parchment paper (11x17" sheet per participant)

10- Small pastry bags for the royal icing (one for each participant)

Scissors

No Cook Mint Patties:

4 T. butter or marg. softened

1/3 cup of light corn syrup

1 tsp. peppermint extract

1/2 tsp. salt

1 lb. sifted powdered sugar–You can do this to your taste. You need enough sugar to ensure recipe comes together in a dough-light consistency.

1 drop each of food coloring

Heart-shaped cookie cutter

Royal Icing:

This version is vegan and made with Aquafaba (the liquid in cans of chickpeas)

- 1/4 cup Aquafaba

- 1 lb to start Powdered/Confectioners Sugar (up to one pound more depending on your needs)

- 1 tsp cream of tartar

- 1 tsp Vanilla

- Water or Lemon Juice to thin prepared icing

- 1.5 tsp of red gel coloring (adjust for desired color)

Instructions

- Provide a safe space for participants to be open, vulnerable, curious, and creative.

- Try to enjoy the process.

- Individually assess how personal identity relates to sexuality.

- Collaboratively develop a definition of consent beyond ‘yes means yes’ and ‘no means no’.

- Understand what Memorable Messages are, how they shape our views, and how to generate positive messages that reflect an understanding of consent.

- Develop a working knowledge of consent in practice via an exercise about rejection and a fun redesign of the infamous Valentine’s Day Conversation Heart.

- Discuss interest and ways to share what has been made/developed.

- Check in with everyone.

Instructions for the No-Bake Mint Patties:

- Thoroughly blend butter, corn syrup, extract and salt in a large bowl.

- Add sugar. Mix with spoon and hands until blended smooth.

- Divide mixture into as many colors as you want to make: knead food coloring into each portion. This takes time. You might start to feel as if the color will never be incorporated. Don’t give up. It comes together. We promise! [Note: You might want to wear plastic/latex gloves for this step.]

- If you want to mimic the pastel colors of the original Conversation Heart candies, be conservative with the food coloring. Add a little color at a time, especially if you are using a gel product, which is very pigmented.

- Shape each colored portion into a round disc and roll out, on one sheet or in between 2 sheets of parchment paper (to reduce sticking) with a rolling pin or large glass bottle (i.e. a wine bottle).

- Flatten out to about ⅛” thickness, and use a heart-shaped cookie cutter (or glass or can) to cut out shapes.

- Let patties dry for several hours on wax or parchment paper-lined sheet trays.

- Patties can be stored in the refrigerator for up to one month and in the freezer for almost an eternity.

Yield: 6 dozen

Instructions for the Royal Icing

-

- Add cream of tartar to a mixing bowl

- Pour in aquafaba

- Mix on medium to high speed with a whisk attachment just until the top of your aquafaba is frothy/foamy

- Turn off the mixer and add in a couple of cups of the powdered sugar.

- Turn the mixer on low until the sugar is mostly incorporated into the aquafaba

- Turn the mixer off and lift the whisk to check the consistency of your icing. The goal is a school-glue type consistency. If it's not there yet, add more powdered sugar about a cup at a time until you achieve it

- Once you achieve the school-glue consistency, add the vanilla

- Turn the mixer up to medium-high speed and let it go for about eight minutes

- After eight minutes or so, turn the mixer off. You should have nice, stiff royal icing! It’s ready for coloring and using for writing

- Store the icing in an airtight container right away – it dries out very quickly – at room temperature for up to a week, in the fridge for a month, or the freezer for pretty much as long as you want.

Background

This resource, or recipe as we like to think of it, addresses the need to expand definitions of consent beyond the binaries of ‘yes means yes’ and ‘no means no,’ and to address the consent education-to-practice gap (Hanebutt, 2021) amongst emerging adults (age 18 – 25 years). It is intended for use by this group as a peer activity, facilitated by friends in a social setting, or as a more organized activity facilitated by a peer councelor, a college dorm Resident Assistant (RAs), etc. However, any group of consenting adults will most likely enjoy and learn something from this recipe.

Through a series of considerations and exercises, this recipe demonstrates that consent is an exchange that can be as complex as the individuals involved. The recipe asks participants to consider their sexual identity and definitions of consent, as well as redesign the messaging of a popular mass-produced product, using the Theory of Memorable Messages proposed in “Tell Me Something Other Than to Use a Condom and Sex Is Scary”: Memorable Messages Women and Gender Minorities Wish for and Recall about Sexual Health. (Rubinsky, Cooke-Jackson, 2017)

The goal of this exercise is to arrive at a deeper, more nuanced understanding of consent by critically analyzing messages we receive about sexuality and consent and how one’s sexual identity impacts their personal relationship to consent. The hope is that participants will also have fun and enjoy the process of getting messy while learning and making something new, and becoming empowered by self-knowledge and consent.

Let’s Get Started…

The below is intended as a guide for the facilitator/s.

This recipe can be facilitated by one or two people with an ideal group size of no more than ten. You can expect this recipe to take 2-2.5 hours.

Creating a Safe Space

Facilitating this activity means creating a space for participants to consider their identities, circumstances, preferences, abilities, strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and the messages and scripts that have influenced them. This this knowledge one can more fully and critically consider how they might apply consent, with specific language that feels in line with their identity. This work takes openness and vulnerability, so it is necessary to check in and ensure that participants are comfortable in the space. Everyone will come to the activity with different experiences and expectations.

Below is a poem about creating safe spaces. It is one way to open the dialogue about what everyone participating in the recipe’s activities wants and needs from the space you are sharing. You can find some additional considerations for creating a safe space for learning and sharing here.

Untitled Poem

by Beth Strano

There is no such thing as a “safe space” —

We exist in the real world.

We all carry scars and have caused wounds.

This space

seeks to turn down the volume of the world outside,

and amplify voices that have to fight to be heard elsewhere,

This space will not be perfect.

It will not always be what we wish it to be

But

It will be our space together,

and we will work on it side by side.

How does this sound to everyone? Do we agree to be present and share this space?

Sexual Identity

Who are you sexually?

According to researcher F. J. J. Viola (2015) in their article, “Ethical Considerations About Consent as the Core of Sexuality Sexologies,” developing a multi-dimensional understanding of consent requires an investigation of an individual’s concept of sex and sexual identity, positionality within systems of power, and abilities to communicate and negotiate consent.

Below are some considerations of all of the things that contribute to who you are sexually. Take some time and answer as many as feel comfortable and applicable. Sexual identities are multi-layered and complex. It’s a long list. It’s also a lot of what contributes to your general identity as a human.

Note: This section is very personal and might bring up strong, difficult, even traumatic feelings for some. Please take care during this section. Do not rush participants. Allow people to pause, take breaks. Reinforce that no one will see the responses to this work. It is not intended to be shared and only intended for participants to carefully examine their sexuality.

For consideration:

- Your identity and sex: What is your gender, race, cultural background? Do you have a disability? Do you have a mental illness? Do you have an STI/STD? How do these intersecting identities relate to your sexual self? Where did you grow up? Where do you live now? What do you do for a living?

- What has your sexual experience been (i.e. you have not engaged in sexual acts, have little experience, have had a lot of sexual encounters, have had non-consensual sexual encounters, have been sexually assaulted, you’re not interested in engaging in sex, etc.)?

- What interests you and what to you like? For example, how feel about touch? Are there touches that you like/don’t like? How do you like to be spoken to? Do you like humor or straight-forward talk? Are you avoidant and do not like confrontation? Do you know what stimulates you sexually? Are there things that you know give you pleasure? Are there things that you are curious about, want to try? Are there things that you do not like and/or do not ever need to do/try?

- Who do you like to be with? (same sex, opposite ses, GNC, anyone/everyone)

- Are there particular bodies that you are attracted to (athletic, curvy, larger, thinner, sinewy?

- How and when are you safe? What makes you feel safe? What makes you feel unsafe?

- Where did you learn these things about yourself?

Check in:

- How did it feel to ask and answer those questions?

- Does anyone want to share any insights about the process (not the identity)?

- Does anyone want to share their answers to the last question?

Defining Consent

What does consent mean to you? Where/how did you learn about consent?

Here are some ways that consent is defined:

From RAINN https://www.rainn.org/understanding-consent

Consent is an agreement between participants to engage in sexual activity. When you’re engaging in sexual activity, consent is about communication—and it should happen every time. The laws about consent vary by state and situation, but you don’t have to be a legal expert to understand how consent plays out in real life.

From Sex Educator, Cory Silverberg in his book, You Know, Sex (2022)

“Consent is another word for giving and getting permission.”

“Consent isn’t only about what we want and how we are feeling. It’s also about the person we are with, what they want, and how they are feeling. And it’s all happening at the same time.”

When getting and giving consent during sexual encounters there are at least three things needed:

Getting consent…

- Asking

- Paying attention

- Checking in

Giving consent…

- Having options

- Thinking clearly

- Choosing for yourself

From the Consent Academy (https://www.consent.academy/what-is-consent.html):

“Consent” is a word with many meanings and applications. It is more than ‘no means no’ and ‘yes means yes’. These simple rules are sometimes helpful, but consent applies to every part of our daily lives – and life can get complicated!

Consent is mostly about feelings, sensations, and power. And feelings, sensations, and power are really complex things.

Consent is about slowing down and taking in the big picture.

One way to understand consent is to consider it a shared feeling created together through a process of constant, collaborative discovery. It’s a feeling that comes from a voluntary agreement (made without coercion) between those with decision-making capacity, knowledge, understanding, and autonomy.

Follow-up questions about consent definitions:

- Do any of the above resonate for you? Why?

- Do you have the words/the vocabulary/ the agency to communicate about consent (asking for permission, saying yes or no or maybe)?

- How do you define consent?

Memorable Messages Research

According to Valerie Rubinsky and Angela Cooke-Jackson’s research, “if individuals interpret a communicative experience as impactful in their lives and they recall it over time, it qualifies as a memorable message.” (Rubinsky and Cooke-Jackson, 2017)

Researcher, Rachel Hanebutt, further asserts that “memorable messages are an essential construct for communicating and critiquing the formal and informal socialization processes that influence young people’s self-concept and provide parameters for their behavior, sexual behavior included” (Ranebutt, 2021) They come from three places (Johnson, et all, 2014):

- Family, friends, peers,

- Personal experiences

- Lessons learned through observation

From a qualitative survey detailed in their research paper, “It Would Be Nice to Know I Exist:” Designing for Ideal Familial Adolescent Messages for LGBTQ Women’s Sexual Health,” Valerie Rubnisky and Angela Cooke-Jackson found negative examples of Memorable Messages can include:

- Homosexuality is wrong.

- Sex is for men (women do not enjoy sex).

- Rape is a normal part of the female experience.

In the same paper, Rubinsky and Cooke-Jackson cited the following examples of positive messages that survey participants wished they received:

- Relationships can look different ways.

- It’s perfectly ok ot experiment with your gender and sexuality, it’s a good thing.

- Asexuality is normal and exists.

- Birth control is a responsible choice that does not make you an immoral person.

- You are a person and regardless of your sexual practices you have worth.

- It’s not a massive deal, you don’t have to just because you are in a relationship, it’s ok to masturbate, sex is not shameful.

Ask participants to make two lists of their own:

Negative messages received from 1.) Family, friends, peers, 2.) Personal experiences, and 3.) Lessons learned through observation.

and

Positive messages received from 1.) Family, friends, peers, 2.) Personal experiences, and 3.) Lessons learned through observation.

Sharing Messages:

Starting with the negative messages, ask if anyone wants to share.

Follow-up questions: How and why do you feel these messages impacted your identity and sexual identity and ideas of consent?

Disrupting Harmful Messages

According to Rachel Hanebutt in their Chapter, “Beyond the Binaries of Sexual Consent,” Memorable messages are an essential construct for communicating and critiquing the formal and informal socialization processes that influence young people’s self-concept and provide parameters for their behavior, sexual behavior included. However, it might also be just as important for harmful messages about sexual consent to be disrupted, as Cooke-Jackson and Rubinsky suggest in Ch. 7 of this volume.” (Hanebutt, 2021)

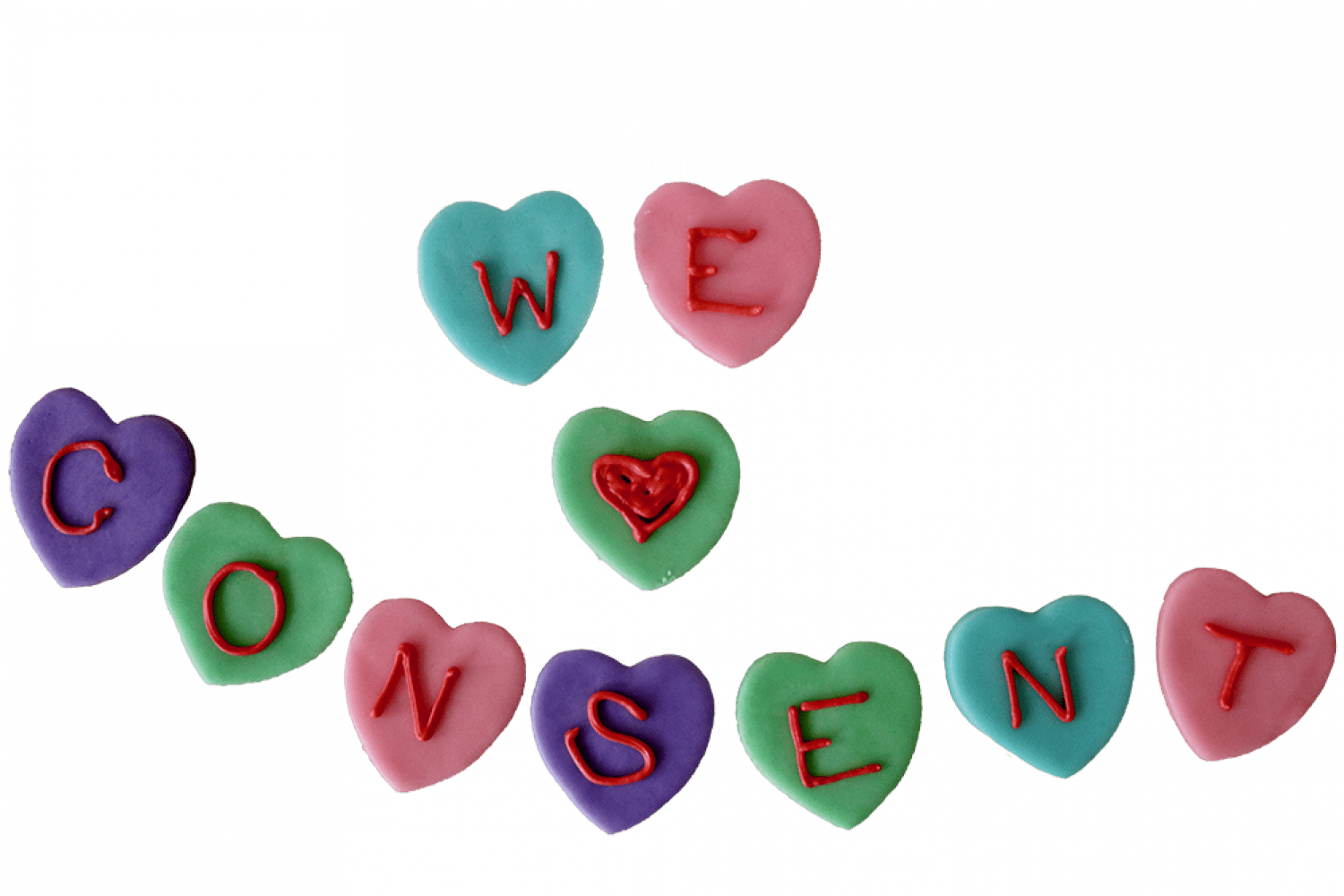

Redesigning Conversation Hearts:

What it would be like to embed better messaging into a mass-produced product like the infamous Conversation Heart Candies that come out around Valentine’s Day every year? What if we were more thoughtful and addressed topics like consent, and promoted self-knowledge and self-acceptance? Could we achieve better conversations, better relationships, and better sex? At the very least, we can try to do better than the antiquated messages, superlatives, orders and directions that appear on Conversation Heart candies, “BE MINE,” “LAUGH,” “CALL ME,” “LOVE,” “YOU + ME,” or the new and ‘improved’ messages, “YAAAAS,” “DM ME,” “LOL.” Maybe we could even deliver on being conversational, and include a question…or two!

So! Design your own Better Conversation Hearts based on your sexual identity and definition of consent, using the No-Bake Mint Patties (actual recipe included above) as your canvas and royal icing as your pen.

[Hand out heart-shaped paper cut-outs, mint-patty dough or pre-cut mint patties (see Baker’s Notes), and royal icing bags– if using.]

Exercise parameters:

- Use 2-3 (shorter) words MAX. Think of words that are not longer than 4-5 letters.

- All caps seem to work best with the icing and clarity.

- Use the colored paper hearts to draft your ideas. If you’re doing this with a group, people can also write the recipes for the mint patties and icing on the other side of the heart.–OLD SCHOOL RECIPE CARD!

- Practice piping the royal icing on the parchment before you turn to the candy.

- Use the paper hearts on the table to work out your ideas.

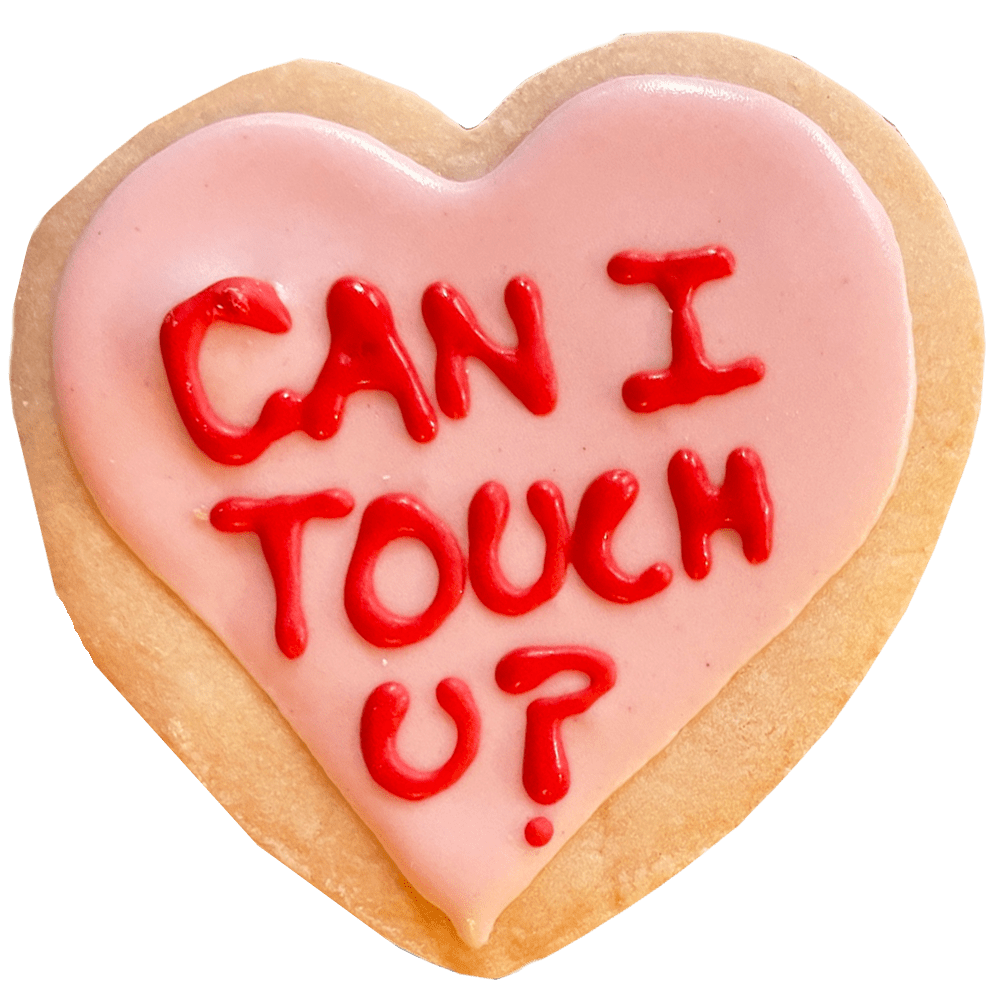

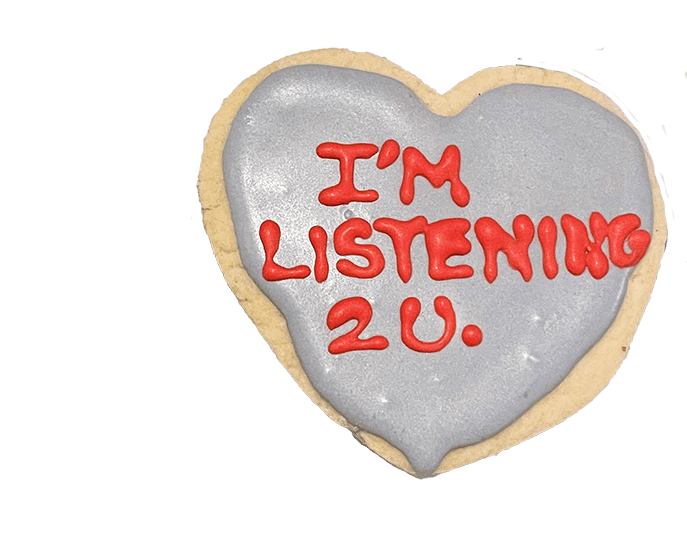

Considerations for YOUR Better Conversation Hearts say:

- Imagine the context of an intimate relationship.

- What are the messages you would like to see in the world related to sex and consent?

- What would you like to say, ask, be asked?

- How can you address the characteristics of consent that you relate to?

- How can you promote healthy/respectful conversations?

- How can you open a dialogue?

- Use honesty and directness without being unkind.

- Assert what you want or like, but not as an order or missive.

- Try a negative, positive, and neutral message.

Checking Out

Everyone take a few deep breaths. How are you feeling? Would anyone like to share what you have learned about consent or yourself? Did this activity feel useful? Practical? Applicable? Fun? Is this something you would recommend to or do with others?

Sharing Your Memorable Messages/Better Conversation Hearts

Are you interested in sharing your Memorable Hearts? Sometimes it feels good to share something that you’ve learned or that you’re proud that you made. In the case of this activity, it can also mean putting positive Memorable Messages into the world, which according to researchers, Rubinsky and Cooke-Jackson, have the “ability to disrupt one another, and for those same messages to serve as potential points of intervention that interrupt the trajectory of harmful or inadequate messages about intimate health.” (Cooke-Jackson, Rubinski, 2021, pg. 91)

Some ways to share/broadcast what you’ve made and learned:

- Agree to document the Memorable Hearts made by your group and share on social media with all of your networks with information about what you learned about consent and why it matters to you.

- Agree to photograph the Memorable Hearts your group has made and use a photo editor to create stickers or temporary tattoos that you can print at home and give as gifts to friends and family or hand out at events along with a definition of consent that the group agrees to, resources you learned about during the activity and/or a link to this recipe for context.

- Plan to do this activity and package the Memorable Hearts you’ve made and give away at an event you attend together (i.e. a sports game, a party, a talk or lecture, etc.) along with a definition of consent that the group agrees to, resources you learned about during the activity and/or a link to this recipe for context.

- Agree to produce a mass quantity of Memorable Hearts with the group’s favorite messages, and sell to raise money for a different organization that the group agrees upholds your collective concept of consent. Some ideas: RAINN, We As Ourselves, ‘me too.’ International, National Women’s Law Center, Transgender Law Center

- Take on the role of facilitator and share this recipe with a different group or club of which you are a member (i.e. a book club, sorority/fraternity, student government, etc.). Keep it going!

Thank you for participating! We hope you had fun while learning something new and important!

Bakers Tips

We recommend having participants all sit around the same table or several smaller tables to share supplies.

Access to a sink is necessary. This recipe is a little messy.

Cover tables with plastic covering or a tablecloth that is not precious.

Set the table/s with a sheet of parchment paper for each participant

Printing the different definitions of consent and placing on the table or posting them on large paper in the space is a nice way for everyone to access and absorb the definitions as you discuss.

Modifications:

- To save time during this activity, the mint patties and icing can be made ahead of time. In this case, participants will only message/decorate the mint patties and not have the experience of making the mint patty dough, but it's faster and less messy.

- For a less tastey but also less messy version of this recipe: You can skip the confection-part of this recipe for time, expense, and ease of clean-up, and only use heart-shaped paper-cut-outs and markers.